Tradução e seleção: André Caramuru Aubert

The mild night

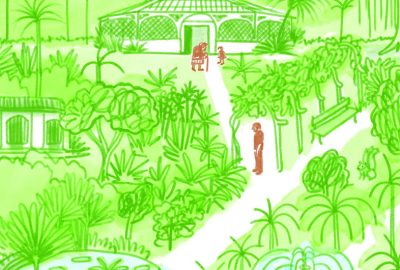

I have taken an armchair into the garden

to enjoy the quietness at the end of May.

This is the way the mild night begins.

I have turned off the only lamp in the kitchen,

blown out the candles and put them away.

I have taken an armchair into the garden.

The lights in the trees can barely be seen

as evening comes and the land falls away.

This is the way the mild night begins.

The road past the house is lit with whitethorn

and grey poplars shine just long enough to say

I have taken an armchair into the garden.

The light on the grass, the blackening sun,

the sunflowers, the sky, the open wind all say

This is the way the mild night begins.

I have forgotten all I have said of pain

to enjoy the quietness at the end of May.

I have taken an armchair into the garden.

This is the way the mild night begins.

A noite serena

Levei uma poltrona para o jardim

para aproveitar a calma do fim de maio.

É assim que a noite serena começa.

Apaguei a única lâmpada da cozinha,

apaguei as velas e as guardei.

Levei uma poltrona para o jardim.

A luz nas árvores mal se distinguia

enquanto a noite chega, a terra esvanece.

É assim que a noite serena começa.

A estrada além da casa está iluminada com espinheiros brancos

e choupos cinzentos brilham apenas o tempo de dizer

Levei uma poltrona para o jardim.

A luz na grama, o sol que escurece,

os girassóis, o céu, o vento aberto, todos dizem

É assim que a noite serena começa.

Esqueci tudo o que já disse sobre a dor

para aproveitar a calma do fim de maio.

Levei uma poltrona para o jardim.

É assim que a noite serena começa.

…

Fiction

None of this is true.

We’re still all

we crack ourselves

out to be.

Our hereafters

have not been laid

in a plot

with my loose ends.

You’re not miles away.

The slow numbers

were never

swayed alone to.

I don’t blame you,

smiling in the mirror

at a face

you’ve just made up.

Ficção

Nada disso é verdade.

Nós ainda somos tudo

que pretendemos

ser.

Nossos futuros

não foram traçados

em um enredo

com minhas pontas soltas.

Você não está a quilômetros de distância.

Os números lentos

Nunca foram

manipulados sozinhos.

Eu não te culpo,

sorrindo no espelho

para um rosto

que acabou de inventar.

…

The woodcock

There are five sides to every story, I’m told.

So let me raise a glass and toast this much,

one last time. Let love come in from the cold,

even if love finds you in someone else’s crush

or someone else in yours that’s grown too long.

Let us greet the leaf, the blossom and the bole.

Let us praise, together, the harbingers of spring

in your step and your girlish way on the mobile.

A galinhola

Toda história tem cinco lados, dizem.

Então deixe-me erguer uma taça e brindar a isso,

uma última vez. Deixe que o amor entre, do frio,

mesmo que o amor te encontre na paixão de outra pessoa

ou outra pessoa na sua, que cresceu demais.

Saudemos a folha, a flor e o tronco.

Louvemos, juntos, os arautos da primavera

em seu passo e seu jeito de menina ao celular.

…

September

It must be a cliché to think, however brief,

that light on a wall and our voices

out in the open are the pieces

we shall look upon in retrospect as a life.

There is a danger of circumstance smothering

even the smallest talk. If a breeze

shakes another colour from the trees

we say a word like withering

without the slightest hint of irony.

After a season of fruitful conversation

and reflective pauses in the garden

we say we know what it means to be lonely.

Today the first moment of autumn tolls

like a refrain from the nineteen thirties.

The voices of friends and courtesies

are interrupted by thunder and the radio crackles.

We shall remember it as the impending doom

and use this afternoon as an example of decay

when there is nothing left for us to say

and September has outstayed its welcome.

Today our clothes will be spoiled by rain.

We shall drag from the lawn the chairs and table

that all summer made us comfortable.

Though all of that remains to be seen.

Setembro

Deve ser clichê pensar, ainda que brevemente,

que a luz na parede e nossas vozes

a céu aberto são os pedaços

que entenderemos, em retrospecto, como uma vida.

Há o perigo de as circunstâncias sufocarem

até mesmo a menor conversa. Se uma brisa

sacode outra cor das árvores

dizemos algo como murchar

sem a menor ponta de ironia.

Após uma temporada de conversas frutíferas

e pausas contemplativas no jardim

dizemos saber o significado de estar só.

Hoje, o momento inicial do outono soa

como um refrão dos anos trinta.

As vozes dos amigos e as boas maneiras

são interrompidas por trovões e estática no rádio.

Lembraremos disso como a desgraça iminente

e usaremos esta tarde como exemplo de declínio

quando não houver mais o que dizer

e setembro deixar de ser bem-vindo.

Hoje, nossas roupas serão arruinadas pela chuva.

Teremos que recolher do quintal as cadeiras e a mesa

que durante o verão nos deram conforto.

Embora isso ainda seja incerto.

…

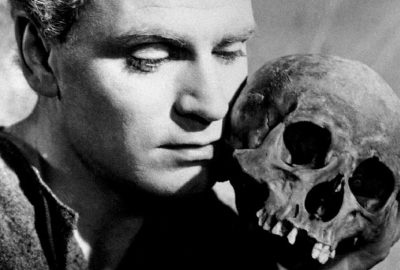

Mengele’s house

It was considered

the finest in its street

on the outskirts of Buenos Aires.

Splashing and screams were heard

during the long July heat

in adjacent gardens.

Nobody has lived there

since the last family fled.

Now and then a researcher comes,

or a would-be buyer

armed with rosary beads

noses around the bedrooms.

Since all the glass

was kicked from a window

by legless students,

the lambency of trees

is free to come and go

in the gutted kitchen.

Out the back are piles

of twigs and compost,

a seventies lawnmower

and aquamarine tiles,

exactly as they were left

by the last owner,

who talked about himself a lot,

chatting across the fence,

but never had the neighbours

past his gate,

and never even once

darkened their doors.

In the neighbourhood

he’s remembered still.

He was the old misery

who had strange kids,

a swimming pool,

and a history.

A casa de Mengele

Era considerada

a mais elegante da rua

nos arrabaldes de Buenos Aires.

Mergulhos e gritos eram ouvidos

durante o interminável calor de julho

nos jardins da vizinhança.

Ninguém mora lá

desde que a última família se foi.

De vez em quando, um pesquisador vem,

ou um possível comprador

armado com contas de rosário

a espreitar os aposentos.

Como o vidro

de uma janela foi estourado

por estudantes bêbados,

o brilho suave das árvores

ficou livre para ir e vir

na cozinha destruída.

Nos fundos, há pilhas

de galhos e adubo,

um cortador de grama dos anos setenta

e ladrilhos azul-marinho,

exatamente como foram deixados

pelo último dono,

que falava muito sobre si mesmo,

conversando do outro lado da cerca,

mas nunca convidou os vizinhos

a cruzarem o portão,

e nunca, nem uma vez

se intrometeu nas casas deles.

Na vizinhança,

ele ainda é lembrado.

Era o velho miserável

que tinha crianças estranhas,

uma piscina,

e uma história.